Introduction

This project was inspired by the clear needs which surfaced through research. One clear example comes from an article in International Journal for Religious Freedom. In the article, “Resilience to Persecution: A Practical and Methodological Investigation” Petri surveys research done on religious communities and their response to persecution. He proposes a resilience assessment tool to categorize how vulnerable communities respond to persecution, then uses empirical research in three Latin American contexts to illustrate the importance of helping vulnerable populations. In the conclusion he states: “As Stout (2010) argues, grassroots religious groups, if they adopt effective strategies, can exercise real influence over policy and promote social justice. Compiling a manual of best practices of the application of coping mechanisms, similar to Gene Sharp’s (1993) catalogue of 198 ‘methods of nonviolent action,’ could also serve a didactic purpose” (Petri 2017:82).

Petri’s understanding of coping mechanisms draws on several previous studies, two of which present broader categories for understanding and analyzing responses to conflict. The first is the book Under Caesar’s Sword which groups Christian responses to persecution in categories of “survival, association, and confrontation” Under Caesar’s Sword: How Christians Respond to Persecution (2018). The second study follows uses a human security lens. Glasius focuses on citizen’s own survival responses to violent conflict through categories of “avoidance, compliance, collective action, and taking up arms” 2012. These categories are indeed helpful places to begin, but additional work is needed to compile best practices in the spirit of what Petri has proposed.

This is the gap this project seeks to fill. We have used the term to “good practices” instead of “best practices” as this acknowledges the complicated problem we are addressing, in alignment with the Cnyefin framework. The name change avoids universalizing any specific practice as fitting for any context and acknowledges the reality that responding to the problem of conflict requires a range of responses.

Researchers and actors in the field of religious studies have access to many streams of information from a plethora of perspectives. Studies of conflict, their sources and contributing factors should and will continue, however this project aims to investigate practices that help prevent, de-escalate, or resolve conflict. This inevitably involves building resiliency, local and foreign actors, and multiple domains of society working together.

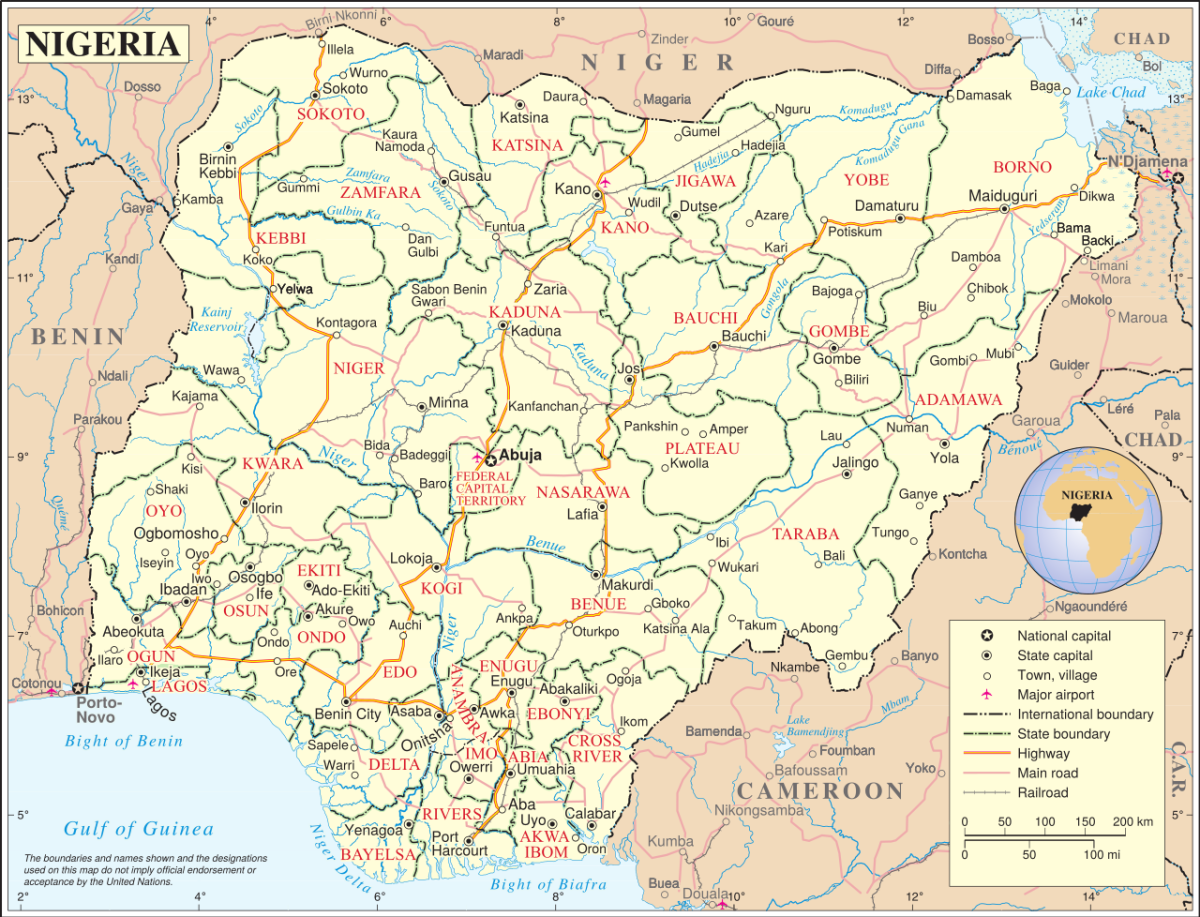

This research endeavor has followed a case study approach. Rooted in studies on religious freedom, this study attempts to generate and collect information on good practices for mitigating conflict that involves religion. The researcher has interviewed individuals and organizational in diverse regional contexts with known pressure against religious communities. This is a first step in an ongoing process of compiling good practices. This initial report follows pilot research in the following areas: Vietnam, Iraq, Nigeria, Columbia, and Mozambique. The case studies aim to generate descriptions of practices that might be profitably replicated and adapted by religious groups in different contexts to promote the cause of religious freedom. This initial report highlights a practice from one of the case studies and mentions next steps.

Excerpts from a selected case in Nigeria

Kenneth, the country lead for Peace Cord International, has been working in religious freedom since 2001. His involvement grew out of his own life experience. In 2001 the violent riots took place between Christians and Muslims. Mass killings and destruction in the city dramatically impacted his father’s business which led to being displaced from their family home and rebuilding from conditions of poverty. This experience led him to study peace building and get involved in religious freedom work.

As a Christian, Kenneth felt that religion had resources to contribute to peace despite the violence often done religion’s name. This led him to a peacebuilding model that he has successfully implemented in several communities. The model focused on Training, Rehabilitation, and EMpowerment. This TREM model is a good practice that is seeing success. This model focused on young men and women, and it aims to build capacity, prevent conflict, and manage conflict in communities. In his context he was able to engage with critical issues like insecurity, drug abuse among young people, and extremism. In some religious communities, it can be difficult for women and youth to have a voice. A peer-oriented, horizontal approach fostered conversation among peer groups, which was a part of developing resiliency.

Kenneth used part of his TREM model within another project called the Joint Initiative for Strategic Religious Action (JISRA). It began in Nigeria and is being implemented in seven countries today. The project is intended to run through 2025. The project promoted FoRB and includes Catholic, Islamic, Protestant, interreligious and secular consortium partners, and local partners. The project is focused on intra-religious, inter-religious, and extra-religious dynamics. The peace building needs to happen at multiple levels.

The first step begins with intrareligious discussion. The religious communities have internal discussions focused on the experiences, challenges, and issues they are facing. This may include Muslim leaders talking about issues in the Mosque or Christians discussing their concerns in churches. These intrafaith groups work through training materials and discuss challenges or communal difficulties in preparation to for the next step. The idea is that when a religious group understands hinderances in meeting their religious obligations and seeks to address it, they will be prepared to see that need in a different faith community. For example, as Muslims consider concrete issues of worship or burying their dead, they might be better prepared to see valid needs in a Christian community.

This step can go on for as long as it takes, but usually twelve months or less. During this time, the outside teams will do training on tolerance, trauma healing, relationship building, and conflict transformation. It is important to not move to the next step of interreligious discussion too soon. Each community should have an opportunity to thoroughly discuss their intrafaith distinctives and air their grievances before engaging a different faith community. Throughout this process, the facilitators will regularly ask if the specific faith community is ready to meet with the other. A readiness to meet is indicated by a willingness to look at internal faults. The community should also indicate a willingness to forgive, without denying real hurts or problems.

The interfaith groups then begin having dialogue about issues in the community and barriers to peace. Often this second step of knowing the other dramatically reduces conflict opportunities. There are theological red lines in Islam and Christianity that are known through both communities, so neither side is asked to deny their commitments. Instead, both communities have an opportunity to recognize that freedom of religion or belief can create common ground to work together on the third pillar, extra-religious dynamics.

In the context of Nigeria this may involve issues of security, the economy or education. Religious groups engage with civil society groups, legislators, and other stake holders. As they develop action plans together, Muslims and Christians face community problems together and build social cohesion.

Practices Observed from Pilot Research

Good practices from other case studies include:

- Mobilizing business and the economic sector to unite communities together. The Business and Religious Freedom Foundation highlighted how the Sunshine nut company is hiring workers from North and South in Mozambique and investing profits into local communities.

- Working with multiple organizations and governments to advocate from the outside in, in difficult contexts like Vietnam.

- Developing a program like Ambassadors for Peace in Iraq and Syria, by building intentional connections with Muslim leaders to reduce active conflict. This program reportedly reduced violence by 42%.

- Starting a peace foundation and focusing on research in Nigeria. Creating well informed reports that avoid sensationalism helps policy makers and parliamentarians face the reality on the ground and increase accountability.

Next Steps

This project is still in its infancy and has several avenues for expansion. We plan to write up case studies based on interviews already conducted in phase one and re-evaluate the plan for the next phase. If you have a case you feel would be a valuable addition please get in touch: kwisdom@iirf.global

Citations

- Glasius, Marlies. “Citizen Participation in Conflict and Post-Conflict Situations.” Address at the occasion of the acceptance of the Special Chair on Citizens’ Involvement in War Situations and Post—Conflict Zones (2012).

- Petri, Dennis P. “Resilience to Persecution: A Practical and Methodological Investigation.” International Journal for Religious Freedom 10, no. 1–2 (2017): 69–86.

- Under Caesar’s Sword: How Christians Respond to Persecution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.